As a cardiologist specializing in the treatment of obesity, I often meet patients who can benefit greatly from the new generation of weight loss drugs that act as agonists such as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). In the recently published CHOOSE trial results, for example, semaglutide (marketed by Novo Nordisk as Wegovy for weight loss and Ozempic for type 2 diabetes) showed a 20% reduction in the risk of heart attack and stroke in obese and non-obese people diabetes and cardiovascular disease. disease, to develop it as a heart disease-modifying drug in people without type 2 diabetes.

Unfortunately, the high demand for these new weight loss drugs has resulted in frustrating, long-lasting shortages. Manufacturers of the two FDA-approved drugs, Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly (tirzepatide, marketed as Zepbound for weight loss and Mounjaro for type 2 diabetes), are struggling to meet high demand.

To ensure continuity of patient care, federal law allows compounding pharmacies to make a “virtual copy” of drugs listed as “currently in short supply” on the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) drug shortage list. Both semaglutide and tirzepatide are on that list. For Americans suffering from obesity and other weight-related diseases, these drugs can be a lifeline.

Despite this, the medical community has widely criticized the use of compounded GLP-1 agonists, even those available from reputable and legal pharmacies.

Of course, high demand has led to the emergence of unregulated companies and counterfeiters who produce low-quality or fake versions of these drugs.

The FDA has detected counterfeit products (masquerading as weight loss drugs) and issued warning letters to stop the distribution of illegally sold semaglutide. “These medicines may be counterfeit, which means they may contain the wrong ingredients, contain too little, too much or no active ingredient, or contain other harmful ingredients,” it warns. Other products use a similar-sounding semaglutide sodium salt, which has uncertain safety and efficacy, and has generated warnings from the FDA and regional boards of pharmacy.

Many of these products are marketed directly to consumers online through websites and social media, with little or no regulatory oversight. This practice is a serious problem, as it may affect patient safety, and should be discouraged.

However, according to a statement from the Alliance for Pharmacy Compounding (APC), compounding pharmacies are not the ones selling these questionable products on the black market, especially on the Internet. This illegal practice has gained media attention and is sometimes wrongly associated with legal pharmacy compounding.

In contrast, legal and certified versions of GLP-1 agonist medications can be found in well-regulated and reputable compounding pharmacies. These pharmacies must comply with all federal and state laws and dispense medications only with a valid prescription from a licensed physician.

Meanwhile, the APC statement notes, Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly have sued compounding companies in several states, questioning, among other things, the purity and potency of certain compounded products.

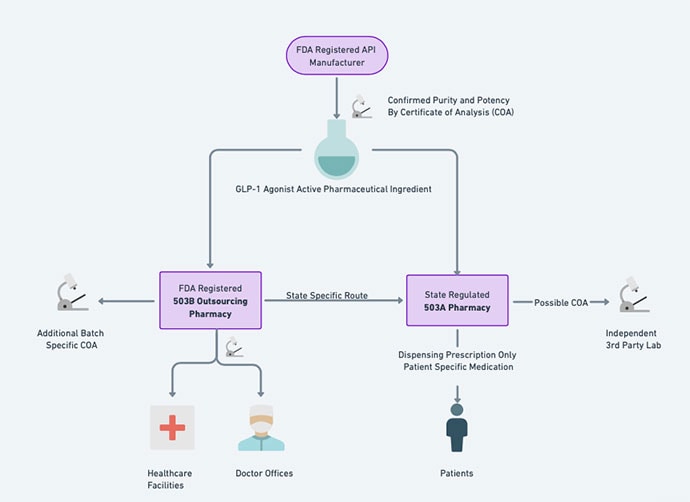

There are different names for compounding pharmacies: 503A and 503B. 503As are state-licensed pharmacies and physicians, and 503B pharmacies are federally regulated dispensing facilities that are strictly regulated by the FDA. This regulation, established after the 2012 meningitis outbreak linked to compounding pharmacy, ensures high quality control and oversight, especially for drugs intended for intravenous or epidural use. These levels exceed those required for subcutaneous injections such as GLP-1 analogues.

Because of this Wild West climate, where compounded drugs can vary in their source, composition, strength, and purity, The Obesity Society, the Obesity Medical Association, and the Obesity Action Coalition published a joint statement advising against the use of compounded drugs. GLP-1 agonists, citing safety concerns and lack of regulatory oversight.

This situation, although intended to ensure patient safety, indirectly raises a serious issue.

By completely rejecting compounded medicines, professionals may unintentionally strengthen the black market and ignore the needs of patients who can benefit from these medicines, contrary to the objectives of the exemption provided in the federal law of compounding during drug shortages. In fact, the presence of unreliable providers highlights the need to direct the public to reliable sources, rather than imposing a complete ban on appropriate medical alternatives.

The joint statement calls GLP-1 compound agonists “counterfeit.” This incorrect exaggeration may be due to a misunderstanding of the integration process and its rules. Legal and controlled pharmacies that include GLP-1 agonists, are “copycats” of FDA-approved drugs, not counterfeits. Recognizing this is critical to maintaining trust in both compounding pharmacies and regulatory agencies.

It is true that “the only manufacturers approved by the FDA of these drugs are the companies that develop the active ingredients of the drugs Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly,” but the joint statement fails to mention the exemption provided by the law that allows the combination of copies of brand drugs. if they are on the missing list.

Compounding pharmacies must obtain active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from FDA-registered facilities, which are required to comply with Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP). This ensures APIs’ quality, potency, and purity, which are essential to the safety and efficacy of compounded medicines.

Compounded drugs are not FDA approved, but they are inherently safe. Compounded medicines include critical drugs such as rehabilitation drugs and antibiotics, and are often used in health care settings, especially when there is a shortage. This raises the question of why combined GLP-1 agonists would be treated differently in such cases.

And in the case of other drugs for obese people at high risk of cardiovascular disease, the FDA-approved brand name may be more of a concern than a combined GLP-1 agonist. Obesity societies advise: “If you can’t find or access GLP-1-based treatments now, there are other treatments available,” experts echo. Although the statement did not specify the names of alternatives, experts have recommended the use of alternatives such as Qsymia and Contrave, despite their potential cardiovascular concerns. This recommendation to the public may not represent a risk-benefit analysis.

Instead of a complete ban on GLP-1 compounded medicines, professional associations can contribute to the solution by creating a “label of approval,” recognizing high-quality compounded medicines. This will contribute to informed decision making for doctors and patients.

Possible Solutions

When prescribing GLP-1 agonists in the treatment of obesity, physicians should consider all of the following measures to ensure patient safety and effective treatment:

Preferred FDA approved products: FDA-approved GLP-1 agonist medications should be the primary option due to their proven safety and efficacy.

Risk-benefit analysis of non-FDA approved products: In cases where FDA-approved options are not available, doctors may consider prescribing a non-FDA-approved copy of the brand-name drug. Prior to this, conduct a thorough risk-benefit analysis with the patient, ensuring that they are fully informed of the potential risks and benefits of using a non-FDA approved product.

Choosing copies of semaglutide in certain cases:In patients with obesity and heart disease, the benefits of using a combined copy of semaglutide, with its cardiovascular disease-modifying properties, may outweigh the risks when compared to other drugs approved by the FDA that may be dangerous to the heart or compared to no antiobesity treatment at all.

Informed consent and monitoring: When prescribing a non-FDA approved version of a GLP-1 agonist, obtaining informed consent from the patient is advised. They should be made aware of the difference between FDA-approved and non-FDA approved versions.

Choosing between 503A and 503B pharmacies: Prescriptions for non-FDA approved GLP-1 agonists can be directed to pharmacies that include 503A or 503B. However, it is advisable to check if the product can be combined with a 503B pharmacy, which is subject to an additional layer of FDA regulation, which provides greater quality assurance.

Clear doctor information: Make sure the prescription clearly states that the compounded GLP-1 agonist must be the base compound without additives.

Requesting a Certificate of Analysis: To further ensure safety, request a Certificate of Analysis from the compounding pharmacy. This provides detailed information of quality and composition about the product.

Continuous monitoring: Continuously monitor the patient’s response to medication and adjust the treatment plan as needed, maintaining regular follow-up.

By adhering to these guidelines, physicians can navigate the dilemma of prescribing GLP-1 agonists in a manner that prioritizes the patient’s well-being, especially in cases where conventional treatment options are limited.

Eldad Einav, MD, is a board-certified cardiologist and Diplomate of the American Board of Obesity Medicine. He is a fellow of the American College of Cardiology and a member of the Obesity Medicine Association. He serves as the medical director of cardiometabolic health at Guthrie Lourdes in Binghamton, New York, and is the founder of myW8/Cardiometabolic Health located in Beverly Hills, California.

This article reflects only the personal views of Dr Einav also should not be construed as representing the official position of Guthrie Lourdes. Dr. Einav served as an advertising spokesperson for Novo Nordisk in 2022. So far, he has not mentioned any GLP-1 compound agonist drugs in his medical practice.

#Truth #Compound #GLP1 #Doctors

Image Source : www.medscape.com